2 Expected Value

The CDF, PMF, and PDF fully characterize the probability distribution of a random variable but contain too much information for practical interpretation. We usually need summary measures that capture essential characteristics of a distribution. The expectation or expected value is the most important measure of the central tendency. It gives you the average value you can expect to get if you repeat the random experiment multiple times.

2.1 Discrete Case

As previously defined, a discrete random variable Y is one that can take on a countable number of distinct values. The probability that Y takes a specific value a is given by the probability mass function (PMF) \pi(a)=P(Y=a).

2.1.1 Expectation

Expected Value (Discrete Case)

The expectation or expected value of a discrete random variable Y with PMF \pi(\cdot) and support \mathcal Y is defined as E[Y] = \sum_{u \in \mathcal Y} u \cdot \pi(u). \tag{2.1}

The expected value can be interpreted as the long-run average outcome of the random variable Y if we were to observe it repeatedly in independent experiments. For example, if we flip a fair coin many times, the proportion of heads will approach 0.5, which is the expected value of the coin toss random variable.

Example: Binary Random Variable

A binary or Bernoulli random variable Y takes on only two possible values: 0 and 1. The support is \mathcal Y = \{0,1\}, and the PMF is \pi(1) = p and \pi(0) = 1 - p for some p \in (0,1). The expected value of Y is:

E[Y] = 0\cdot\pi(0) + 1\cdot\pi(1) = 0 \cdot(1-p) + 1 \cdot p = p.

For the variable coin, the probability of heads is p=0.5 and the expected value is E[Y] = p = 0.5.

Example: Education Variable

Using the variable education with its PMF values introduced previously, we can calculate the expected value:

\begin{align*} E[Y] &= 4\cdot\pi(4) + 10\cdot\pi(10) + 12\cdot \pi(12) + 13\cdot\pi(13) \\ &\quad + 14\cdot\pi(14) + 16\cdot \pi(16) + 18 \cdot \pi(18) + 21 \cdot \pi(21) \\ &= 0.032 + 0.55 + 4.716 + 1.027 + 2.03 + 1.248 + 3.924 + 0.504 \\ &= 14.031 \end{align*}

So, the expected value of education is 14.031 years, which corresponds roughly to the completion of short-cycle tertiary education (ISCED level 5).

2.1.2 Conditional Expectation

Previously, we introduced conditional probability distributions, which describe the distribution of a random variable given that another random variable takes a specific value. Building on this foundation, we can define the conditional expectation, which measures the expected value of a random variable when we have information about another random variable.

Conditional Expectation Given a Fixed Value

For a discrete random variable Y with conditional PMF \pi_{Y|Z=b}(a), the conditional expectation of Y given Z=b is defined as:

E[Y|Z=b] = \sum_{u \in \mathcal{Y}} u \cdot \pi_{Y|Z=b}(u)

This formula closely resembles the unconditional expectation, but uses the conditional PMF instead of the marginal PMF. The conditional expectation E[Y|Z=b] can be interpreted as the average value of Y we expect to observe, given that we know Z has taken the value b.

Example: Education Given Marital Status

Let’s examine the conditional PMFs of education given marital status studied previously.

For unmarried individuals (Z=0): \pi_{Y|Z=0}(a) = \begin{cases} 0.01 & \text{if } a = 4 \\ 0.07 & \text{if } a = 10 \\ 0.43 & \text{if } a = 12 \\ 0.09 & \text{if } a = 13 \\ 0.10 & \text{if } a = 14 \\ 0.09 & \text{if } a = 16 \\ 0.19 & \text{if } a = 18 \\ 0.02 & \text{if } a = 21 \\ 0 & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}

For married individuals (Z=1): \pi_{Y|Z=1}(a) = \begin{cases} 0.01 & \text{if } a = 4 \\ 0.03 & \text{if } a = 10 \\ 0.38 & \text{if } a = 12 \\ 0.07 & \text{if } a = 13 \\ 0.17 & \text{if } a = 14 \\ 0.06 & \text{if } a = 16 \\ 0.25 & \text{if } a = 18 \\ 0.03 & \text{if } a = 21 \\ 0 & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}

The conditional expectation of education for unmarried individuals is:

\begin{align*} E[Y|Z=0] &= 4 \cdot 0.01 + 10 \cdot 0.07 + 12 \cdot 0.43 + 13 \cdot 0.09 \\ &\quad + 14 \cdot 0.10 + 16 \cdot 0.09 + 18 \cdot 0.19 + 21 \cdot 0.02 \\ &= 13.75 \end{align*}

The conditional expectation of education for married individuals is:

\begin{align*} E[Y|Z=1] &= 4 \cdot 0.01 + 10 \cdot 0.03 + 12 \cdot 0.38 + 13 \cdot 0.07 \\ &\quad + 14 \cdot 0.17 + 16 \cdot 0.06 + 18 \cdot 0.25 + 21 \cdot 0.03 \\ &= 14.28 \end{align*}

We observe that the expected education level is higher for married individuals (14.28 years) compared to unmarried individuals (13.75 years), which suggests a dependence between marital status and education.

2.1.3 Conditional Expectation Function (CEF)

So far, we have used E[Y|Z=b] to denote the conditional expectation of Y given a specific value b of Z. This is a fixed number for each value of b. A related concept is the Conditional Expectation Function, denoted as E[Y|Z] without specifying a particular value for Z.

Conditional Expectation Function (CEF)

The conditional expectation function E[Y|Z] represents a random variable that depends on the random outcome of Z. It is a function that maps each possible value of Z to the corresponding conditional expectation:

E[Y|Z] = m(Z) \quad \text{where} \quad m(b) = E[Y|Z=b]

Here, m(\cdot) is the function that represents the CEF, mapping each possible value of Z to the corresponding conditional expectation.

The CEF is random precisely because it is a function of the random variable Z. Before we observe the value of Z, we cannot determine the value of E[Y|Z]. Once we observe Z, the CEF gives us the expected value of Y corresponding to that specific observation. This makes E[Y|Z] a random variable whose value depends on the random outcome of Z. In contrast, E[Y|Z=b] is a deterministic scalar non-random value.

For our marital status example, the CEF is:

E[Y|Z] = m(Z) = \begin{cases} 13.75 & \text{if } Z = 0 \text{ (unmarried)} \\ 14.28 & \text{if } Z = 1 \text{ (married)} \end{cases}

In our population, the marginal PMF of married is \pi_Z(a) = \begin{cases} 0.4698 & \text{if } a = 0 \ (\text{unmarried})\\ 0.5302 & \text{if } a = 1 \ (\text{married}) \\ 0 & \text{otherwise}. \end{cases}

Using these values the PMF of E[Y|Z] is: \pi_{E[Y|Z]}(a) = P(E[Y|Z] = a) = \begin{cases} 0.4698 & \text{if } a = 13.75 \\ 0.5302 & \text{if } a = 14.28 \\ 0 & \text{otherwise}. \end{cases}

2.1.4 Law of Iterated Expectations (LIE)

Law of Iterated Expectations

For two random variables Y and Z: E[Y] = E[E[Y|Z]]

This elegant equation states that the expected value of Y can be found by first calculating the conditional expectation of Y given Z (which gives us the random variable E[Y|Z]), and then taking the expected value of this random variable. In other words, we are taking the expectation of the conditional expectation.

The Law of Iterated Expectations is a fundamental tool in econometrics with numerous applications. It is particularly important for understanding the properties of estimators in the presence of conditioning variables like in regression analysis.

To understand why this law holds, let’s consider an intuitive argument based on the law of total probability. For discrete random variables, the law of total probability tells us that we can find the overall probability of an event Y=a by considering all possible scenarios Z=b that could lead to that event. More precisely, P(Y=a) equals the weighted sum of conditional probabilities P(Y=a|Z=b) across all possible values b of Z, where each conditional probability is weighted by P(Z=b): \pi_Y(a) = \sum_{b \in \mathcal{Z}} \pi_{Y|Z=b}(a) \cdot \pi_Z(b)

The LIE follows a similar logic. We can think of the overall expectation of Y as a weighted average of conditional expectations E[Y|Z=b] across all possible values of Z, with each conditional expectation weighted by the probability of the corresponding Z value:

E[Y] = \sum_{u \in \mathcal{Z}} E[Y|Z=u] \cdot \pi_Z(u)

The right hand side is precisely what E[E[Y|Z]] means: take the conditional expectation function E[Y|Z] and average it over all possible values u\in \mathcal Z of Z, where \mathcal Z is the support of Z.

For our education and marital status example, the LIE gives us:

\begin{align*} E[Y] &= E[E[Y|Z]] \\ &= E[Y|Z=0] \cdot \pi_Z(0) + E[Y|Z=1] \cdot \pi_Z(1) \\ &= 13.75 \cdot 0.4698 + 14.28 \cdot 0.5302 \\ &= 6.460 + 7.571 \\ &= 14.031 \end{align*}

This matches exactly with our directly calculated expected value of 14.031 years from the marginal PMF.

2.1.5 Conditioning Theorem (CT)

Conditioning Theorem / Factorization Property

For two random variables Y and Z:

E[ZY|Z] = Z \cdot E[Y|Z]

To see this, let’s first consider the case for a specific value Z=b:

E[bY|Z=b] = \sum_{u \in \mathcal{Y}} b \cdot u \cdot \pi_{Y|Z=b}(u) = b \sum_{u \in \mathcal{Y}} u \cdot \pi_{Y|Z=b}(u) = b \cdot E[Y|Z=b]

When we consider this factorization across all possible values of Z rather than a fixed value b, we get the general form of the Conditioning Theorem: E[ZY|Z] = Z \cdot E[Y|Z].

The conditioning theorem states that we can factor out the conditioning variable Z from the conditional expectation. The intuition is that when we condition on Z, we’re essentially treating it as if we already know its value, so it behaves like a constant within the conditional expectation. Since summation is linear and constants can be factored out, Z can be factored out of E[ZY|Z].

This theorem is particularly useful in econometric derivations, especially when working with regression models.

For example, in our marital status context, if we want to compute E[Z Y|Z] (the conditional expectation of education multiplied by marital status, given marital status), we get:

E[Z Y|Z] = Z \cdot E[Y|Z] = \begin{cases} 0 \cdot 13.75 = 0 & \text{if } Z = 0 \text{ (unmarried)} \\ 1 \cdot 14.28 = 14.28 & \text{if } Z = 1 \text{ (married)} \end{cases}

I’ve evaluated your draft for the “Continuous Case” subsection, and it’s a good start. Here’s my suggested improved version with better organization, more detailed explanations, and enhanced examples:

2.2 Continuous Case

Now, let’s extend our discussion of expected values to continuous random variables, which are characterized by probability density functions (PDFs) rather than probability mass functions (PMFs).

Expected Value (Continuous Case)

The expectation or expected value of a continuous random variable Y with PDF f_Y(u) and support \mathcal{Y} is defined as E[Y] = \int_{\mathcal{Y}} u f_Y(u) \, du = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} u f_Y(u) \, du. \tag{2.2}

Intuitively, this integral calculates a weighted average of all possible values of Y, where the weight of each value is given by its density. This is analogous to the discrete case, where we computed a weighted sum. The key difference is that continuous random variables have infinitely many possible values within their support, requiring integration rather than summation.

2.2.1 Conditional Expectation for Continuous Variables

For continuous random variables, the conditional expectation given that Z=b is defined similarly:

Conditional Expectation (Continuous Case)

For a continuous random variable Y with conditional PDF f_{Y|Z=b}(u), the conditional expectation of Y given Z=b is:

E[Y|Z=b] = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} u f_{Y|Z=b}(u) \, du

The same principles of conditional expectation functions (CEF) that we discussed for discrete variables apply here as well. The CEF E[Y|Z] = m(Z) is a random variable that depends on the random outcome of Z, where m(b) = E[Y|Z=b] is the function mapping each possible value of Z to the corresponding conditional expectation.

2.2.2 Examples with Continuous Random Variables

Example 1: Uniform Distribution

A random variable Y follows a uniform distribution on the interval [0,1] if its PDF is constant across this interval:

f(u) = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if} \ u \in[0,1], \\ 0 & \text{otherwise.} \end{cases}

The expected value is calculated as:

E[Y] = \int_{-\infty}^\infty u f(u) \, du = \int_{0}^1 u \cdot 1 \, du = \int_{0}^1 u \, du = \left. \frac{u^2}{2} \right|_{0}^1 = \frac{1}{2}

So the expected value of a uniform random variable on [0,1] is exactly \frac{1}{2}, the midpoint of the interval. More generally, for a uniform distribution on [a,b], the expected value is \frac{a+b}{2}.

Example 2: Wage Distribution

Let’s return to our wage variable from Part 1. Suppose the wage distribution in our population has the following PDF:

f(u) = \begin{cases} \frac{1}{20}e^{-u/20} & \text{if} \ u \geq 0, \\ 0 & \text{otherwise,} \end{cases}

This represents an exponential distribution with parameter \lambda = 1/20. The expected value is:

E[Y] = \int_{0}^{\infty} u \cdot \frac{1}{20}e^{-u/20} \, du = \frac{1}{20} \int_{0}^{\infty} u \cdot e^{-u/20} \, du

Using integration by parts or leveraging the known mean of an exponential distribution (1/\lambda), we get E[Y] = 20 EUR per hour.

Example 3: Wage Given Education

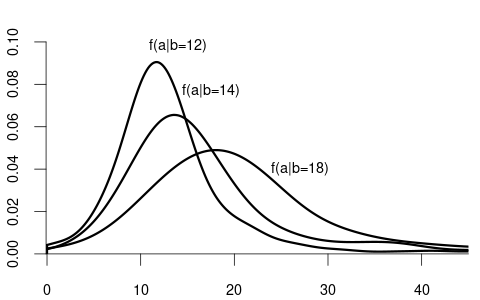

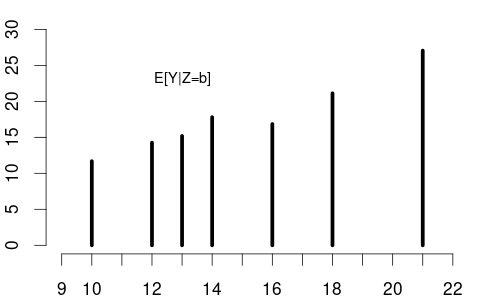

From Figure 1.7 (b), we saw that the conditional distribution of wage given education varies substantially:

These different distributions lead to different conditional expectations:

- E[Y|Z=12] = 14.3 EUR/hour

- E[Y|Z=14] = 17.8 EUR/hour

- E[Y|Z=18] = 27.0 EUR/hour

The CEF plot is given below:

The increasing conditional expectations reflect the positive relationship between education and wages. This dependency confirms that education and wages are not independent random variables.

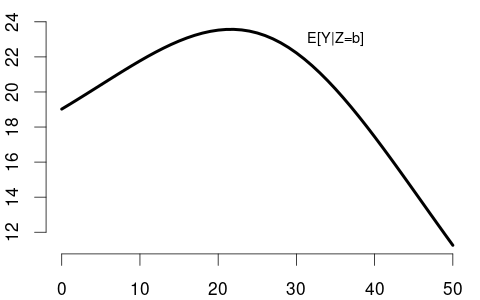

Example 4: Wage Given Experience

Now consider the relationship between wage (Y) and years of experience (Z). Labor economics theory suggests that wages typically increase with experience but at a diminishing rate. Suppose empirical analysis reveals that the conditional expectation of wage given experience level b follows a quadratic form:

m(b) = E[Y|Z=b] = 19 + 0.5b - 0.013b^2

This functional form captures the initial increase in wages with experience (positive linear term 0.5b) and the diminishing returns over time (negative quadratic term -0.013b^2).

For some specific values:

- m(5) = E[Y|Z=5] = 21.2 EUR/hour

- m(10) = E[Y|Z=10] = 22.7 EUR/hour

- m(20) = E[Y|Z=20] = 23.8 EUR/hour

- m(30) = E[Y|Z=30] = 22.3 EUR/hour

The conditional expectation function is maximized at the point where its derivative equals zero:

\frac{d}{db}m(b) = 0.5 - 0.026b = 0 \implies b = \frac{0.5}{0.026} \approx 19.2

This suggests that, on average, wages peak at around 19.2 years of experience in this population.

As a function of the random variable Z, the CEF is:

E[Y|Z] = m(Z) = 19 + 0.5Z - 0.013Z^2

This is itself a random variable because its value depends on the random outcome of Z.

2.3 General Case

We can define the expected value of a random variable Y in a unified way that applies to both discrete and continuous cases using its CDF F_Y(u).

Expected Value (General Definition)

E[Y] = \int_{-\infty}^\infty u \, \text{d}F_Y(u) \tag{2.3}

This formula uses the Riemann-Stieltjes integral, which generalizes the familiar Riemann integral. To understand this, recall that the standard Riemann integral \int_a^b g(x) \, dx is defined as: \int_a^b g(x) \, dx = \lim_{n \to \infty} \sum_{i=1}^{n} g(x_i^*) \Delta x_i where [a,b] is partitioned into n subintervals [x_{i-1}, x_i] of width \Delta x_i = x_i - x_{i-1}, and x_i^* is any point in the i-th subinterval. The limit is taken as the maximum width of all subintervals approaches zero.

In contrast, the Riemann-Stieltjes integral \int_a^b g(x) \, dh(x) is defined as: \int_a^b g(x) \, dh(x) = \lim_{n \to \infty} \sum_{i=1}^{n} g(x_i^*) \Delta h_i where \Delta h_i = h(x_i) - h(x_{i-1}) represents the increment in the function h over the i-th subinterval.

Intuitively, while the standard Riemann integral weighs the function values by increments in the x-axis, the Riemann-Stieltjes integral weighs them by increments in another function, allowing us to seamlessly handle both continuous distributions (where we integrate against a smooth CDF) and discrete distributions (where the integrator function has jumps).

For infinite intervals, as in \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} u \, dF_Y(u), the integral is defined as: \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} u \, dF_Y(u) = \lim_{a \to -\infty, b \to \infty} \int_a^b u \, dF_Y(u)

2.3.1 Special Case: Continuous Random Variables

For a continuous random variable Y with PDF f_Y(u), the CDF F_Y(u) is differentiable with \frac{dF_Y(u)}{du}=f_Y(u)

Hence: \text{d}F_Y(u) = f_Y(u) \, \text{d}u

Substituting this into our unified definition: E[Y] = \int_{-\infty}^\infty u \, \text{d}F_Y(u) = \int_{-\infty}^\infty u \cdot f_Y(u) \, \text{d}u

This recovers the standard definition for continuous random variables we saw earlier.

2.3.2 Special Case: Discrete Random Variables

For a discrete random variable, the CDF F_Y(u) has jumps at each point u \in \mathcal{Y} where Y can take values. The size of each jump is: \Delta F_Y(u) = F_Y(u) - F_Y(u^-) = P(Y=u) = \pi_Y(u) where F_Y(u^-) = \lim_{\varepsilon \to 0, \varepsilon > 0} F_Y(u - \varepsilon) is the left limit of F_Y at u.

For discrete variables, the Riemann-Stieltjes integral simplifies to a sum over these jumps: E[Y] = \int_{-\infty}^\infty u \, \text{d}F_Y(u) = \sum_{u \in \mathcal{Y}} u \cdot \Delta F_Y(u) = \sum_{u \in \mathcal{Y}} u \cdot \pi_Y(u)

This matches our earlier definition for discrete random variables.

2.3.3 Why the General Case Matters

The unified approach to expected values offers several important advantages:

Conceptual and practical simplicity: Using the CDF as the foundation emphasizes that distinguishing between discrete and continuous random variables isn’t critically important for defining expectations. In econometric practice, expectations are computed without needing to categorize the distribution first, as the same principles apply regardless of distribution type.

Handling mixed and exotic distributions: Many real-world variables have distributions that don’t fit neatly into pure categories—like wages with both continuous values and “spikes” at round numbers, or insurance claims that are zero with positive probability but continuous for positive values. The general definition also accommodates more exotic theoretical cases like the Cantor distribution.

Unified theoretical development: For developing econometric theory, having a single definition simplifies proofs and ensures results apply broadly without requiring separate cases for different distribution types, allowing us to focus on understanding the properties and relationships between random variables.

2.3.4 General Definition of Conditional Expectation

Just as we can define the expected value in a unified way, we can also define conditional expectation in a general form that applies to all types of random variables.

Conditional Expectation (General Definition)

For random variables Y and Z, the conditional expectation of Y given Z=b is defined as: E[Y|Z=b] = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} u \, \text{d}F_{Y|Z=b}(u) where F_{Y|Z=b}(u) is the conditional CDF of Y given Z=b.

Similarly, for any random vector \boldsymbol Z = (Z_1, \ldots, Z_k)', the conditional expectation of Y given \boldsymbol Z = \boldsymbol b is: E[Y|\boldsymbol Z=\boldsymbol b] = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} u \, \text{d}F_{Y|\boldsymbol Z=\boldsymbol b}(u)

This definition uses the Riemann-Stieltjes integral with respect to the conditional CDF. For continuous random variables with conditional PDF f_{Y|Z=b}(u), this becomes: E[Y|Z=b] = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} u \cdot f_{Y|Z=b}(u) \, \text{d}u

For discrete random variables with conditional PMF \pi_{Y|Z=b}(u), it simplifies to: E[Y|Z=b] = \sum_{u \in \mathcal{Y}} u \cdot \pi_{Y|Z=b}(u)

The conditional expectation function (CEF) is then defined as: E[Y|Z] = m(Z) where m(b) = E[Y|Z=b] for each possible value b that Z can take. This makes E[Y|Z] a random variable whose value depends on the random outcome of Z.

Similarly, if \boldsymbol Z is a vector, we have: E[Y|\boldsymbol Z] = m(\boldsymbol Z) where m(\boldsymbol b) = E[Y|\boldsymbol Z = \boldsymbol b].

This can also be extended to conditioning on a n\times k matrix of random variables \boldsymbol X (e.g., a regressor matrix), which gives E[Y|\boldsymbol X]. This extension is particularly important in econometrics for regression analysis.

2.3.5 Conditional Expectation and Independence

When two random variables Y and Z are independent, the conditional distributions simplify considerably. As we saw in the first section, independence means that the conditional distribution of Y given Z=b is the same as the marginal distribution of Y. This fundamental property has important implications for conditional expectations.

Conditional Expectation and Independence

If random variables Y and Z are independent, then:

E[Y|Z=b] = E[Y] \quad \text{for all } b

And consequently:

E[Y|Z] = E[Y]

In other words, when Y and Z are independent, knowing the value of Z provides no information about the expected value of Y. The conditional expectation equals the unconditional expectation for every possible value of Z.

To understand why this holds, recall that for independent random variables, the conditional CDF equals the marginal CDF. Using the general definition of conditional expectation:

E[Y|Z=b] = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} u \, \text{d}F_{Y|Z=b}(u) = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} u \, \text{d}F_Y(u) = E[Y]

The middle equality holds because F_{Y|Z=b}(u) = F_Y(u) for all u when Y and Z are independent.

This means that the conditional expectation function E[Y|Z] = m(Z) reduces to a constant function:

m(b) = E[Y] \quad \text{for all } b

For example, recall our coin flip example from Part 1, where we noted that the distribution of a coin toss remains the same regardless of whether a person is married or unmarried:

F_{Y|Z=0}(a) = F_{Y|Z=1}(a) = F_Y(a) \quad \text{for all } a

where Y represents the coin outcome and Z is the marital status. In this case, E[Y|Z=0] = E[Y|Z=1] = E[Y] = 0.5, reflecting that the expected outcome of a fair coin toss is 0.5 regardless of the marital status of the person tossing it. Hence, E[Y|Z] = E[Y] for this example.

2.3.6 Expected Value of Functions

Often, we are interested not just in the expected value of a random variable Y itself, but in the expected value of some function of Y, such as Y^2 or \log(Y).

Expected Value of a Function

For any function g(\cdot), the expected value of g(Y) is: E[g(Y)] = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} g(u) \, \text{d}F_Y(u)

For conditional expectations: E[g(Y)|Z=b] = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} g(u) \, \text{d}F_{Y|Z=b}(u)

The conditional expectation function is E[g(Y)|Z]=m(Z), where m(b) = E[g(Y)|Z=b].

As discussed above for the different cases, \text{d}F_Y(u) can be replaced by the PMF or the PDF: \int_{-\infty}^\infty g(u) \, \text{d}F_Y(u) = \begin{cases} \sum_{u \in \mathcal Y} g(u) \pi_Y(u) & \text{if} \ Y \ \text{is discrete,} \\ \int_{-\infty}^\infty g(u) f_Y(u)\,\text{d}u & \text{if} \ Y \ \text{is continuous.} \end{cases}

Example: Transformation of a Binary Variable

For instance, if we take the coin variable Y and consider the transformed random variable \log(Y+1), the expected value is: \begin{align*} E[\log(Y+1)] &= \log(1) \cdot \pi_Y(0) + \log(2) \cdot \pi_Y(1) \\ &= \log(1) \cdot \frac{1}{2} + \log(2) \cdot \frac{1}{2} \\ &= \frac{\log(2)}{2} \approx 0.347 \end{align*}

This approach allows us to compute expectations of arbitrary functions of random variables.

2.4 Properties of Expectation

The general expected value operator has several important properties. Here we focus on three fundamental properties: linearity, the Law of Iterated Expectations, and the Conditioning Theorem.

2.4.1 Linearity

Linearity of Expectation

For any constants a, b \in \mathbb{R} and random variable Y: E[a+bY]=a+bE[Y]

The same property holds for conditional expectations: E[a+bY|Z] = a + bE[Y|Z]

This property tells us that the expectation of a linear transformation of a random variable equals the same linear transformation of the expectation.

To understand why this holds, consider the definition of expectation using the Riemann-Stieltjes integral: E[a+bY] = \int_{-\infty}^\infty (a+bu) \, \text{d}F_Y(u)

We can separate this into two parts: \int_{-\infty}^\infty (a+bu) \, \text{d}F_Y(u) = \int_{-\infty}^\infty a \, \text{d}F_Y(u) + \int_{-\infty}^\infty bu \, \text{d}F_Y(u)

The first integral equals a because \int_{-\infty}^\infty \text{d}F_Y(u) = 1 for any probability distribution. The second integral equals b\cdot E[Y]. Combining these results gives us a + bE[Y].

2.4.2 Law of Iterated Expectations (LIE)

Law of Iterated Expectations

For any random variables Y and Z: E[Y]=E[E[Y|Z]]

The LIE states that the expected value of Y can be found by first taking the conditional expectation of Y given Z, and then taking the expectation of this result over the distribution of Z.

This result relies on the law of total probability, which connects marginal and conditional distributions. For discrete random variables, this law states: \pi_Y(u) = \sum_{b \in \mathcal{Z}} \pi_{Y|Z=b}(u) \cdot \pi_Z(b)

For continuous random variables with densities, the law takes the form: f_Y(u) = \int_{-\infty}^\infty f_{Y|Z=b}(u) \cdot f_Z(b) \, db

In the general case using CDFs, the law of total probability is expressed as: \text{d}F_Y(u) = \int_{-\infty}^\infty \text{d}F_{Y|Z=b}(u) \, \text{d}F_Z(b)

When we evaluate E[E[Y|Z]], we are calculating: E[E[Y|Z]] = \int_{-\infty}^\infty E[Y|Z=b] \, \text{d}F_Z(b)

Expanding the inner conditional expectation: E[E[Y|Z]] = \int_{-\infty}^\infty \left(\int_{-\infty}^\infty u \, \text{d}F_{Y|Z=b}(u)\right) \, \text{d}F_Z(b)

Applying the general form of the law of total probability, this double integral simplifies to: E[E[Y|Z]] = \int_{-\infty}^\infty u \, \text{d}F_Y(u) = E[Y]

2.4.3 Conditioning Theorem (CT)

Conditioning Theorem

For any random variables Y and Z, and any measurable function g(\cdot): E[g(Z)Y|Z]=g(Z)E[Y|Z]

The Conditioning Theorem states that when we condition on Z, we can factor out any function of Z from the conditional expectation.

To see why this holds, consider a specific value Z=b. The conditional expectation becomes: E[g(Z)Y|Z=b] = E[g(b)Y|Z=b] = g(b)E[Y|Z=b]

The first equality follows because g(Z) = g(b) when Z=b. The second equality uses the linearity property of expectation, treating g(b) as a constant.

Since this relationship holds for every possible value of Z, we have the general result: E[g(Z)Y|Z]=g(Z)E[Y|Z]

2.5 Heavy Tails: When Expectations Fail to Exist

Our previous discussions assumed that expected values and covariance matrices exist, but this isn’t always guaranteed. Some probability distributions have such slow decay in their tails that moments of certain order may be infinite or undefined. These “heavy-tailed” distributions present special challenges for statistical analysis.

2.5.1 Infinite Expectations

Infinite Expectation

A random variable Y has an infinite expectation if: E[|Y|] = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} |u| \, \text{d}F_Y(u) = \infty

When this occurs, the expected value E[Y] either diverges to positive infinity, negative infinity, or is not well-defined due to both positive and negative parts of the integral diverging.

In such cases, the sample mean does not converge to any finite value as the sample size increases.

The sample mean of i.i.d. samples from most distributions converges to the population mean as sample size increases (a property known as consistency). However, there are exceptional cases where consistency fails because the population mean itself is infinite.

2.5.2 Examples of Distributions with Infinite Moments

Pareto Distribution

The simple Pareto distribution with parameter \alpha = 1 has the PDF: f(u) = \begin{cases} \frac{1}{u^2} & \text{if} \ u > 1, \\ 0 & \text{if} \ u \leq 1, \end{cases}

The expected value is: E[Y] = \int_{-\infty}^\infty u f(u) \ \text{d}u = \int_{1}^\infty \frac{u}{u^2} \ \text{d}u = \int_{1}^\infty \frac{1}{u} \ \text{d}u = \log(u)|_1^\infty = \infty

Since the population mean is infinite, the sample mean cannot converge to any finite value and is therefore inconsistent.

St. Petersburg Paradox

The game of chance from the St. Petersburg paradox is a discrete example with infinite expectation. In this game, a fair coin is tossed until a tail appears; if the first tail is on the nth toss, the payoff is 2^n dollars. The expected payoff is: E[Y] = \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} 2^n \cdot \frac{1}{2^n} = \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} 1 = \infty

This infinity arises from the infinite sum of 1’s, reflecting the unbounded potential payoffs in the game.

Cauchy Distribution

The Cauchy distribution (also known as the t-distribution with 1 degree of freedom) has the PDF: f(u) = \frac{1}{\pi (1+u^2)}

The Cauchy distribution presents a fascinating case where the sample mean of n observations has exactly the same distribution as a single observation, regardless of how large n becomes. This means the sample mean does not converge to any value as sample size increases.

t-Distribution with Few Degrees of Freedom

- Cauchy distribution (t_1): No finite moments

- t_2 distribution: Finite mean but infinite variance

- t_3 distribution: Finite variance but infinite skewness

- t_4 distribution: Finite skewness but infinite kurtosis

More generally, for a t-distribution with m degrees of freedom: E[Y^k] < \infty \text{ for } k < m E[Y^k] = \infty \text{ for } k \geq m

2.5.3 Real-World Examples

Heavy-tailed distributions arise in many real-world phenomena where extreme events and large outliers are common:

- Financial returns: Stock market crashes and extreme price movements

- Income and wealth distributions: Extreme wealth concentration

- Natural disasters: Extreme earthquakes, floods, or storms

Although it is rare for a distribution to have a truly infinite mean in practice, some real-world distributions nonetheless exhibit extremely heavy tails, which can lead to values that appear as “outliers” in the data. Such outliers are not mere anomalies, but part of the distribution’s intrinsic behavior. For instance, certain assets in financial markets can experience massive price swings, and wealth distributions in some populations show extreme inequality. These very large or very small observations make conventional estimates (e.g., sample means) extremely volatile or unreliable. In econometrics and statistics, recognizing even the possibility of heavy tails is crucial for choosing estimation and inference methods that can handle such data effectively.